The Bay Psalm Book is notable for being the first book printed in the North American British colonies. It was published in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1640. For reference, the House of the First Printing Press in the Americas, also established by colonizers, began printing books in Mexico City in 1539. The Bay Psalm Book was an original translation of the Psalms, meant to be used in worship by the 3,500 families living in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The group of translators included Richard Mather, whose grandson Cotton Mather is known for his involvement in the Salem Witch Trials. It would go on to be republished in several editions and remained in use for about 100 years. If you’ve ever been to a Christian church, you’ve likely seen battered old copies of hymn books tucked into slots in the back of every pew. How could such a book be worth this astronomical price? To understand the answer, we have to dig into what the Bay Psalm Book really means in the world of books.

Books vs. Texts

The Bay Psalm Book is more known as a book than as a text. Which is to say, the book is the physical object. Its existence is significant in both the history of the book and the history of the United States. The text is the content of the book. An example of an important text, as we’re on the topic of Biblical translations, is the King James Version of the Bible. Of course, a first printing of that version from 1611 is a rare and valuable book, but the text of the KJV has persisted across the centuries and is still what many contemporary Christians use in their worship. By contrast, the translations of the psalms found in the Bay Psalm Book are not particularly well known or well liked today. Here’s a sample from its version of the beloved 23rd Psalm: It’s not a version you’ll find many people reciting. I find myself adopting a Yoda voice when I try to read it aloud — clunky it is. want therefore shall not I, Hee in the folds of tender-grasse, doth cause mee downe to lie: To waters calme me gently leads Restore my soule doth hee: he doth in paths of righteousnes: for his names sake leade mee.

Textual Curiosities

Some books are known for their beauty as objects or the achievement in printing, like the oversized and lavish The Birds of America. The Bay Psalm Book isn’t really one of those either. Riddled with typos and inconsistencies, it’s evidence of the printers’ inexperience. One charming example is the two successive paragraphs of text that include the spellings “metre,” “meeter,” and “meetre.” The whole book is digitized if you want to go searching for errors yourself. If printing text accurately is difficult, forget music. The book contains the text of psalms meant to be sung, but there’s no printed musical notation. Luckily it wasn’t necessary. The translations of the psalms were intentionally designed to fit common melodies that would be familiar to those engaging in communal singing. Imagine trying to translate a poem, but it has to be singable to “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.” That was the task the translators set for themselves. So if the text is more curiosity than anything else, what is the meaning of the book? In a word, freedom.

The Bay Psalm Book and Freedom of Religion

Perhaps you, like me, are someone who thinks the United States was founded on incredibly flawed principles (stolen Indigenous land and chattel slavery to name two of the biggies). Still, the significance of the printed word in U.S. history is undeniable. Freedom is a fraught and oft-misunderstood term in this country, but freedom to practice a religion and freedom of speech were ideals that sprouted from the presence of a printing press brought to the colonies. In order for the Puritans to practice Christianity the way they wanted to, they colonized Massachusetts and created the Bay Psalm Book. The book was one of the things that represented religious freedom for them in the colonies because the Psalms were translated to be used for congregational singing. Puritans believed in communal singing during worship — something some of England’s other churches had been eschewing in favor of dedicated choirs. That 1,700 copies were printed to be distributed among 3,500 families shows how serious the printers were taking the efforts to change religious practice.

The Bay Psalm Book and Free Speech

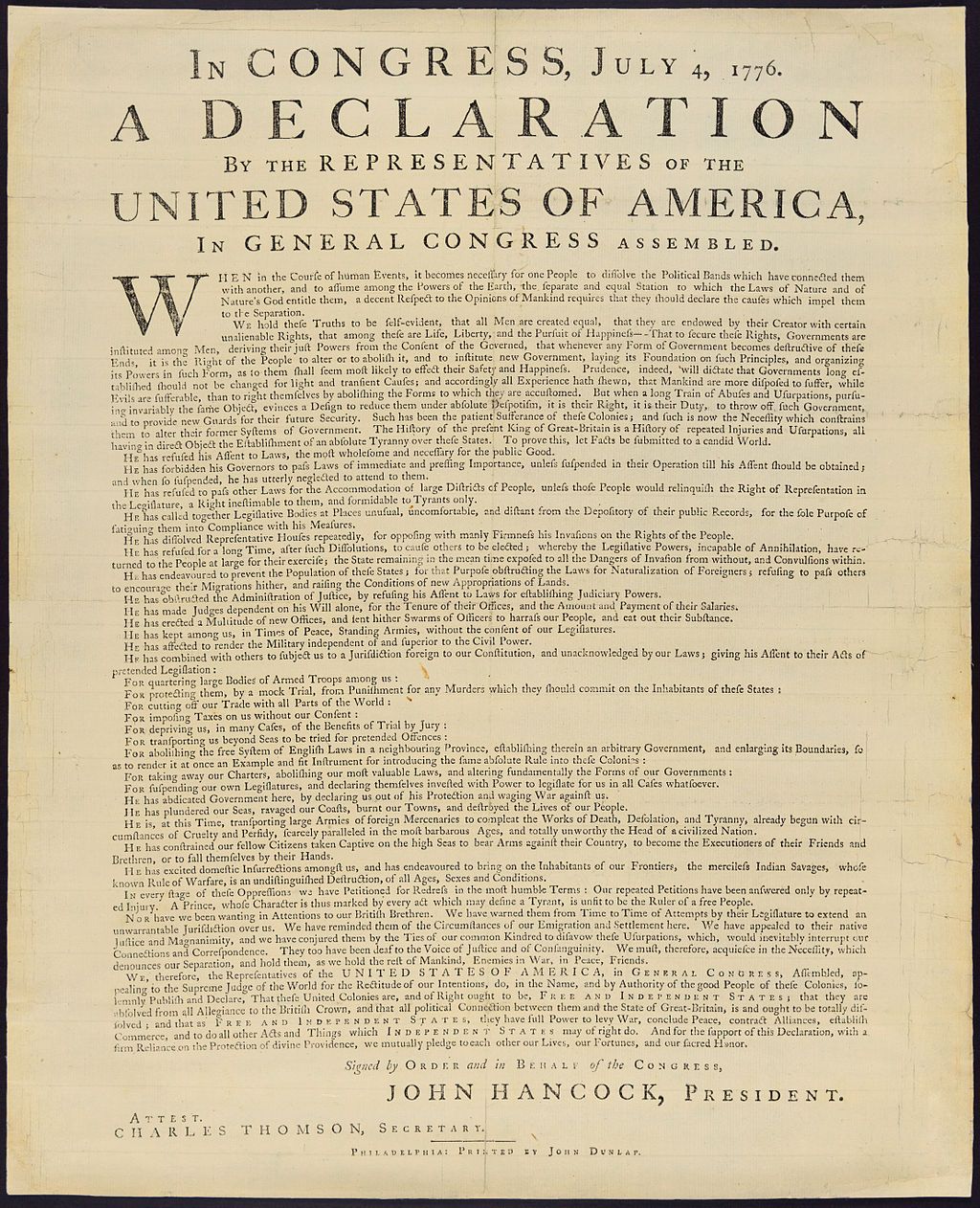

There are numerous printed documents intertwined with the dawning American revolution. Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, for one. And a fact that not enough people know is that the Declaration of Independence was originally a document printed on a press and distributed widely in a form known as the Dunlap broadside. The calligraphic version we love to watch Nicolas Cage steal is not the real Declaration of Independence. In fact, there’s an argument made beautifully in this essay from the American Antiquarian Society that points at the insidious nature in caring too much about those seemingly singular handwritten artifacts. If we thought of them as the mass-produced editions of a document that they were, would it be a little easier to think of them as something deserving of an update every now and again? The mass production of the Bay Psalm Book showed how printed materials spread wide without government interference could change practices and bring about a measure of freedom. What’s fascinating is that only 11 of the 1,700 copies printed survived.

The rarity of the Bay Psalm Book

Of the 11 known copies, almost half came from Boston’s Old South Church. Like many details of the Bay Psalm Book’s narrative, the Old South Church is a storied part of American history. Samuel Adams gave the signals that started the Boston Tea Party from there. Both Benjamin Franklin and celebrated enslaved poet Phyllis Wheatley were among the congregation in the 18th century. The remainder of the 1,700 copies originally printed? Likely used to death. This statistic, a less than 1% survival rate, shows how the Bay Psalm Book differs from another rare book like the Gutenberg Bible. Somewhere between 160 and 185 copies of that bible were printed, and almost 50 substantially complete copies remain. Considering how easy it is to lose books to disasters like fire and flood, Gutenberg Bibles were obviously treasured from the start. Bay Psalm Books, in contrast, were meant to be in a congregation’s hands. The significance of the Bay Psalm Book, along with its rarity, help to explain why it cost so much at auction. The 2013 auction made headlines, but it wasn’t the first time this book set a record.

Setting the Record

In fact, the Bay Psalm Book has set the record for the all-time high price for a printed book twice. The first time was in 1947, when the trust of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, founder of the Whitney Museum of American Art, decided to sell Whitney’s copy of the Bay Psalm book to benefit a hospital. The copy ended up going to Yale’s Beinecke Library, but only after a fierce bidding war and a miscommunication. A. S. W. Rosenbach, the rare book seller whose Philadelphia library is well worth a visit, was acting as Yale’s agent in the auction. He managed to outbid Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney (Gertrude’s son). But the closing bid of $151,000 was much more than Yale had fundraised toward their goal of acquiring the book. Rosenbach said he’d fill in the $49,500 gap with a loan. Yale took him up on that, but understood it as a donation. Yale and Rosenbach’s brother argued over the arrangement via blisteringly polite letters until they dropped the matter in 1952. The second time the record was broken was in November 2013, when the Old South Church sold its penultimate copy for $14.2 million to David Rubenstein, a billionaire history buff. This was the first time a copy had gone up for sale since the 1947 auction. As a side note, other handwritten manuscripts have sold for more than the Bay Psalm Book. A manuscript of the Book of Mormon and a notebook of Leonardo da Vinci’s are notable examples. But is the Pay Psalm Book the most valuable printed book in the world?

Understanding Price vs. Value

It’s easy to think the book that has fetched the highest price at auction — twice, no less — must be the most valuable. But remember: rare books are rare! For some of the most prized rare books, like the Gutenberg Bible, Shakespeare’s First Folio, Audubon’s The Birds of America, and the Bay Psalm Book, the auctions are rare, too. The printed book currently in second place to The Bay Psalm Book price-wise is The Birds of America, of which there are 119 known copies. It goes up for sale more often, most recently in December 2019 for $6.6 million. Another copy sold in 2010 for $11.6 million. Shakespeare’s First Folio, of which there are 235 known copies, generally fetches a lower price than the Bay Psalm Book. Mills College sold their copy in 2020 for almost $10 million. A complete Gutenberg Bible hasn’t gone up for auction since 1978. It would likely shatter the record if and when that happens. So in terms of potential price, The Bay Psalm Book is certainly not the most valuable book. And there are books rarer than any of these. Books printed in Europe before 1500 are called incunables, and of those, plenty exist as only one copy. One especially notable book, the first printing of Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, has two known copies. One is at New York’s Morgan Library, and the other at the John Rylands Library in Manchester, England. William Caxton, thought to be England’s first printer, printed them in 1485. If one of those copies were to go up for sale, would it set the record? What would happen if a third copy popped up? Truly impossible to say. But if I were a villain setting up a rare book forging operation, that might be what I’d try to replicate.

True Crime Side Bar

Speaking of forgery. (We’ll get there, I promise). Reverend Joseph Glover was a driving force behind the Bay Psalm Book. He planned on setting up a printing press in Massachusetts but died aboard the ship transporting the press. His widow Elizabeth made his vision possible by tapping Stephen Day to do the printing. He was Glover’s indentured servant and a locksmith by trade. John Winthrop, governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, noted the establishment of Day’s printing house in Cambridge in a diary entry. He wrote, “The first thing which was printed was the freeman’s oath; the next was an almanack made for New England by Mr. William Peirce Mariner; the next was the Psalms newly turned into metre.” Anyone who watched the Netflix documentary Murder Among the Mormons just felt a little shiver down their spine (just me?). The freeman’s oath was the first printed document of any kind in the North American British colonies. It’s also the very document forged by murderer Mark Hoffman. No real copies of this loyalty pledge have ever turned up; it’s a true white whale in the collectors’ world. But the mere idea of it makes the printing house that produced The Bay Psalm Book rather legendary.

In Conclusion

Of the 11 copies of the Bay Psalm Book known to exist, ten of them are in the United States. The outlier belongs to the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford. The outsized price of the book and its concentration within U.S. borders has a lot to say about the way the United States prizes the parts of history that demonstrate our claimed ideals. Assigning value to books is an odd endeavor. I think again of poet Phyllis Wheatley, who was baptized at the Old South Church. Maybe she held some later edition of a Bay Psalm Book or sung some version of its text. She was callously named after the ship that transported her from West Africa. Her story is a sad and brutal chapter in American history, and the fact that she died young and in poverty is a travesty. Would a copy of her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, ever raise $14 million at auction? What would it mean if it did? For everyone but billionaires and rich institutions, owning a piece of book history like the Bay Psalm Book is mere fantasy. Still, we can collect what reflects value to us. It could be books, zines, comics, or concert flyers. Whatever interests you, collect it. And by stewarding these materials through generations, we can have a say in how the future sees our values.