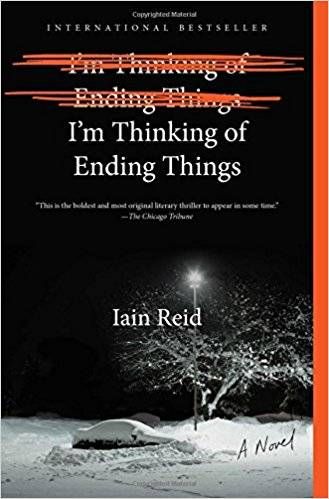

There are many ways one can remind themselves of the fantasy of horror in film. I recently listened to the episode of The Scaredy Cats Horror Show podcast that features A Nightmare on Elm Street. In the episode, the hosts discuss the film with Rachel Talalay, a self-proclaimed former scaredy cat who worked on the movie. She described imagining Freddy Kruger at the snack table between takes to help quell her fears. I find it much more difficult to do that during reading. There’s no covering my eyes, frantically scrolling through Facebook, or diving nose-first into a tub of popcorn. There’s no hiding from the horror between the covers of a book. I was reminded of this feeling of inescapability while reading Iain Reid’s I’m Thinking of Ending Things. Once I started, the need to know what came next overwhelmed me. From the very first chapter I felt threatened by a sense of menace. That feeling continued to build until the final sentence. I closed the book, set it down beside my bed, turned off the light, and just sat there waiting, desperately hoping I would settle into a deep sleep. My efforts were fruitless. A few moments later I opened the notes section of my phone and typed away to release some of that dread, or at least try to get to the bottom of why I was feeling so damned bothered. As hard as it is to do, I will refrain from divulging anything about the plot. I will say that I’m Thinking of Ending Things left me questioning what, if anything, is scarier than being stuck. The cover shows the phrase, “I’m thinking of ending things,” written and crossed out, then written again, above a car completely covered by snow, and it prompts us to consider thoughts or actions we aren’t quite ready, or are too frightened, to commit fully to. You know, the kind of thoughts that persist, almost as though they themselves have come to life, until they become indelibly engraved in our minds. The paralyzing fear of potential never realized is perhaps the scariest prospect posed by the book. And that fear of unrealized potential poses its own web of disturbing questions: Are the feelings that attend a fantasy any less real for being impelled by a web of thoughts that gravitate around something unreal? On the flip side, if the love we feel for those we care about is based on a fantasy, does it make the love any less real? “What could be more real than a thought,” asks Jake, the narrator’s boyfriend. That is a question that made me squirm, and as I closed the book I had nowhere to turn but to burrow more deeply into my own anxieties about the positive and negative thoughts and feelings that constitute the sticking point between realizing our potential and fantasizing about it. I wonder if the film adaptation will stick with me the same way.