“Why can’t they leave politics out of it?” these benighted fools moan, right before waxing nostalgic about Captain America punching Hitler in the face. “Remember the good old days when comics weren’t full of social justice warriors?” No, as a matter of fact, I don’t remember. Because that time never existed. This article takes you on a whirlwind tour of superheroes’ long history of battling for social justice. It’s not always pretty, but it’s important to remember—especially these days—that superheroes are about more than power fantasies and colorful costumes.

Let’s Start at the Start

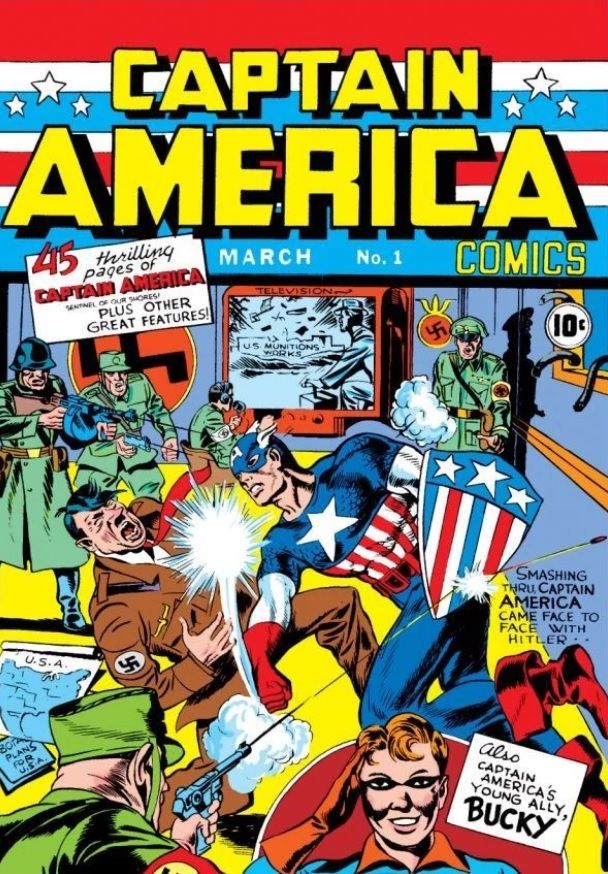

The tradition of pitting superheroes against the real world is as old as the medium itself. Action Comics #1, the first official superhero comic, has Superman put the smackdown on corrupt politicians and an abusive husband. No alien invaders or mole men here; just very recognizable, very grounded villains. A little over a year after Superman leaped his first tall building, World War II began. The United States wouldn’t get involved for a couple of years, but that didn’t stop (mostly Jewish) comic book creators from taking potshots at Hitler almost immediately. After Pearl Harbor, they started skewering Japan (just…all of Japan) as well. The results of these efforts are mixed. At one extreme, you have Captain America, an iconic hero who has grown far beyond his original purpose of punching Nazis. (Though he occasionally still does that.) At the other, you have some of the most offensive stories ever printed in comics. Everyone from Aquaman to Wonder Woman used anti-Japanese racial slurs, and Captain Marvel (Billy, not Carol) once triumphantly crowed about putting Japanese saboteurs in a concentration camp. Childhood innocence, indeed. Even the most well-intentioned stories don’t always age well. In one hilariously naïve tale from 1940, Superman grabbed Hitler and Stalin by the scruff of the neck and dumped them at League of Nations headquarters for punishment. That’s right: Superman ended World War II all by himself before America fired a shot. Suck it, Steve Rogers! Reality soon caught up to the comics industry. Once Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, almost every superhero from every publisher went to war. But now that real live Americans were out fighting, superheroes couldn’t undermine their sacrifice by magically ending the conflict. Superman, rather than deposing dictators literally single-handed, was relegated to protecting the home front and encouraging war bond purchases.

It’s Over Over There

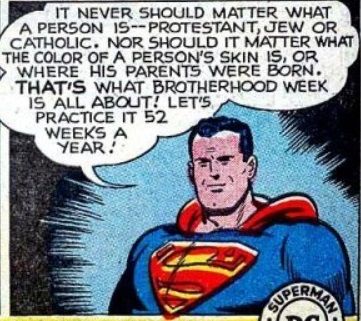

After World War II, superheroes lost popularity for a while. Postwar audiences wanted to chill with a romance or funny teen comic, not read about more fighting. Captain America clashed with communism for a short while before being put on ice (literally, as it turned out). Worse, in the 1950s, some congressmen smelled an opportunity to win over the “moral crusader” demographic and launched an investigation into how comic books contributed to juvenile delinquency. (They didn’t, but that was beside the point.) The result: the Comics Code Authority, a draconian set of rules that prevented comics from depicting or discussing sensitive issues like drugs, corruption, and werewolves. Comics didn’t give up the fight against real-world problems entirely, however. DC produced a series of public service advertisements in which Superman and Batman, their most popular heroes, denounced racism and encouraged children to be tolerant of people from different religions and cultures. The Superman radio show, meanwhile, took on the Ku Klux Klan. Over at Marvel, the Avengers were fighting racism in the form of Klan expies, the Sons of the Serpent, as early as 1966. But of course, this was still the ’50s and ’60s. At the same time as Marvel and DC published these relatively progressive stories, they also published stuff like Tales of Suspense, wherein Iron Man fought some cringe-worthy depictions of Asian communists. Because it’s okay to be racist if your targets are communists, I guess?

Drugs and Politics

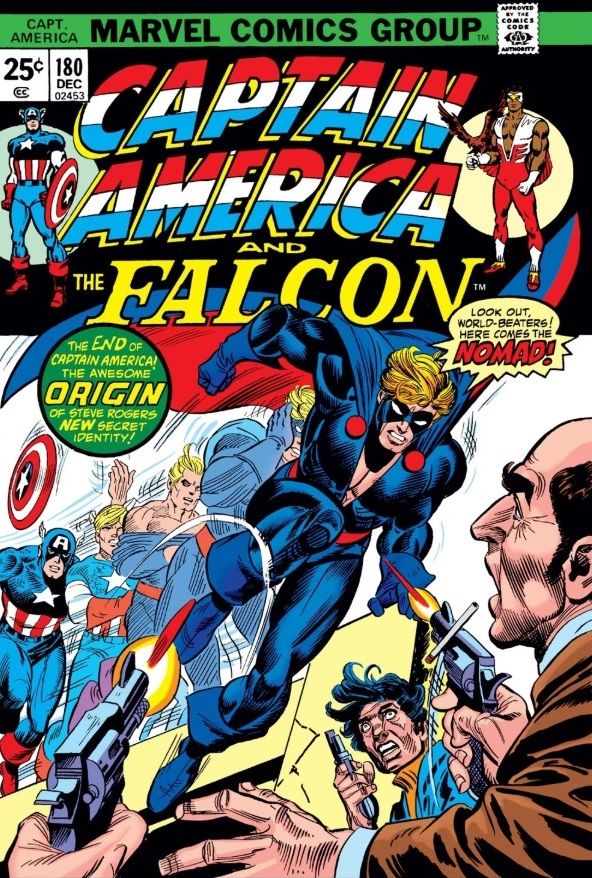

By the early 1970s, Marvel and DC were tired of kowtowing to the Comics Code Authority and decided to see just how far they could push it. DC transformed Green Lantern into Green Lantern/Green Arrow. The conservative Lantern and the liberal Arrow were constantly at loggerheads over every major issue of the day, from poverty to pollution to indigenous rights. They weren’t necessarily sensitive about it all, mind, but they tried. Marvel, meanwhile, published Amazing Spider-Man #96, which featured Spidey rescuing a drug addict who jumped off a roof in the mistaken belief that he could fly. In the next issue, Peter’s friend, Harry Osborn, admitted he was hooked on various pills. The CCA pitched a fit over this storyline and refused to put their stamp of approval on the covers, even though the explicit message of the story was that Drugs Are Bad. But Marvel’s gambit would have long-reaching consequences. Their anti-drug story proved that a publisher no longer had to cower before the censors; they could push back and still be successful. Suddenly, drugs were everywhere in superhero comics. DC presented their own anti-drug tale, Green Lantern/Green Arrow #85–86, about Green Arrow’s sidekick developing a heroin addiction. Later in the decade, Iron Man would begin his ongoing struggle with alcoholism. But drugs weren’t the only issue that ‘70s comics had something to say about. In the wake of Watergate, with the entire country reeling from Nixon’s crimes, Captain America was left reeling as well. By this time, Cap had long since returned to the superhero scene. Nazi-punching was no longer his raison d’être, but he was still a symbol of American idealism. How would he react when it turned out Richard “I’m Not a Crook” Nixon was, indeed, a crook? Despite the comics code allegedly banning the depiction of “Government officials and respected institutions” in a disrespectful manner, in Captain America #175, Cap confronted Number One, the leader of the evil Secret Empire. One was secretly a high-level government official intent on becoming a dictator. His face is never shown, but Cap’s reaction to unmasking him, plus the fact that the final confrontation takes place in the Oval Office, make it pretty clear it’s Tricky Dick. After Number One’s suicide (yes, really), Cap had such a personal crisis that he temporarily stopped being Captain America.

And Now

As the medium matured, superhero comics got a lot more nuanced and thoughtful about dealing with social justice issues (suicidal presidents aside). When they’re written well, superheroes are still out there fighting the good fight. One of the Green Lanterns had to deal with a gay friend being beaten by homophobes. Superman has swooped in to save Latino workers from a xenophobic white terrorist. But these actions, while incredibly important, are a real come-down from the Golden Age of the ’30s and ’40s. John Zatara has not forced Jair Bolsonaro into exile. (Yes, he did that to Hitler.) Captain America has not slugged Kim Jong-Un. Comics are, believe it or not, more subtle than they used to be. Look at how they dealt with 9/11. Virtually every Marvel superhero lives in New York City. What, were they all on vacation that day? How could this possibly happen with the likes of the Fantastic Four, Doctor Strange, and the Avengers in the vicinity? And why didn’t they immediately go to Afghanistan, knock Bin Laden unconscious, and drag him before the United Nations? Simple: because it would have been disrespectful to the victims otherwise. Marvel, I’m sure, concocted an excuse for why all their heroes were suddenly unavailable, just as DC gave Hitler the Spear of Destiny, a magic superhero-repelling artifact that prevented the Justice Society from stopping the war at the source. It’s silly, of course, but so is the concept of superheroes in general. It’s just another thing we as fans have to hand wave and accept. Well, most of us have accepted it. A few attempts have been made to revive the superhero’s original method of dealing with real-world problems, i.e. hit it until it stops. In Spider-Gwen Annual #1, an alternate-universe Donald Trump, now called M.O.D.A.A.K. (Mental Organism Designed as America’s King), gets beat up by a black, female Captain America. Marvel got away with this for three very important reasons. One, it’s an alternate universe. Two, it “punches up,” mocking only those in power. And three, it ends without a clear resolution. Sure, it’s implied that Captain America will defeat M.O.D.A.A.K. and Hydra, but the story ends mid-fight. Unlike Superman ending World War II, there’s a real possibility that Cap won the battle but still has a war to win. Unfortunately, there are stories which miss all of those points entirely. Holy Terror is about a quote-unquote “superhero” seeking revenge on the Middle Eastern terrorists who bombed his city. It’s not a comic so much as a disturbing rant filled with Islamophobia so vile you can practically see Frank Miller frothing at the mouth as he writes it. The alleged goal of Holy Terror was to recreate the good old Hitler-punching days of yore. Perhaps as a parody it would have worked, or perhaps not. We’ll never know, because Miller took this project as seriously as any Golden Age writer screaming about the Japanese, with all the bigotry that implies.

The Thrilling Conclusion

The best-remembered scene from Green Lantern/Green Arrow happens in Issue 76. An old black man walks up to Green Lantern and demands to know why he spends so much time protecting aliens and so little time protecting black people. Green Lantern can only hang his head in shame. By 1970s standards, the scene was groundbreaking. Today, it comes off as a bit preachy, and personally, I find the question disingenuous. True, superheroes have fallen prey to contemporary prejudices often enough that I could write a thesis on it. But even a brief look back at the history of superhero comics shows they have always supported and fought for social justice. They have also shown a capacity to learn. Progress is never a straight line, but for the most part, comic book creators now realize that you can’t minimize real suffering for the sake of a story, or to make yourself feel better. The trick seems to be creating a scenario where the heroes can triumph, but not too much. DC Comics: Bombshells does this very well. It is set during World War II and pits DC’s greatest heroines against enemies like the Joker’s Daughter and Tenebrus: magical, fictional beings who have allied themselves with the Nazis. Adolf Hitler is, with apologies to Monty Python, Monster Not Appearing in this Comic. And that’s probably for the best. The movie Captain America: The First Avenger already made this point, but it’s worth repeating: watching a superhero thwack a terrible person is fun in an instant gratification sort of way, but it doesn’t help the people suffering under that terrible person. It’s a fantasy. And while superheroes may live in a fantasy world, the readers don’t. Cap can punch Hitler all he wants, but Hitler will still be there in the real world doing real, terrible things. Reality is the superhero’s true kryptonite. So no, superheroes can’t just fly in and fix everything. They never could. That is perhaps the most important and most ironic thing they teach us: you can’t depend on someone bigger and stronger than you to save the day. Even in worlds awash with caped heroes, ordinary citizens still have a part to play, whether it’s buying war bonds or throwing rocks to distract Green Goblin or just being kind to someone who needs it. Maybe superheroes can’t save the world, but their ongoing fight for social justice can inspire us to keep trying to save it ourselves.