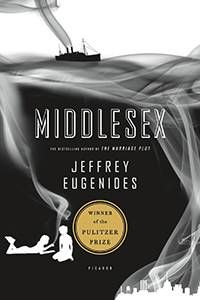

Kindle in hand, I settled into my transatlantic flight with a thin blanket and antiseptic-smelling pillow, burying myself in Middlesex. The book is great. It lives up to the hype. The settings and characters are rich, diving into the Greek immigrant experience, watching a family struggle to find their footing and eventually succeeding, grasping that elusive American Dream. Of course, this is literary fiction, so nothing is simple or happy for long. Family strife bubbles under the surface and the protagonist—grandchild of the immigrants that begin the novel—is unknowingly intersex. Alongside the fish-out-of-water immigrant story is a coming-of-age for a young woman who doesn’t even realize her (Cal chooses to be he by the end of the book, but is she early on) body is different until puberty rears its head. For her, puberty is late, and when it does come, it is but a whisper of the raging scream that affects her fellow teens. My own intersex story wasn’t the same. I was born as gendered as a Ken doll. My name was Baby for three days while doctors waited on the results of a chromosome test. XY I had three surgeries at ages two and three to build the appropriate boy bits from bladder skin grafts, descend my testicles, and make sure I could pee like a “real” boy. For as long as I can remember, I’ve known I was different. When puberty hit, a severe kidney infection that affected my vas deferens revealed the full extent of my differences. Like Cal and most intersex people, I cannot have children. For me (because being intersex is not a singular experience, and I cannot speak for others), being intersex means being acutely aware of my body at all times. I don’t look the same as most men. Every locker room comes with an extra layer of anxiety. Urinals mean standing uncomfortably close to the porcelain to block wandering eyes. While the prospect of a new sexual partner is exciting for many, for me it was someone else who had to be told the whole story, prepared for what they were about to see and feel, and the limitations that created. This is the one thing I found missing from Eugenides’s writing: the sense of the body. There are great observations, deep dives into the science of what makes Cal intersex, and a heaping helping of the psychological wrestling between genders that comes with the intersex discovery. Unlike Cal, I always knew about my differences, though I regarded them as “birth defects” until well into my late 30s, when I first thought of myself as intersex. But Middlesex never gave me that physical intimacy with Cal, the level-5 psychic distance John Gardner famously wrote about in The Art of Fiction. I wanted Gardner’s “Snow. Under your collar, down inside your shoes, freezing and plugging up your miserable soul.” translated into Middlesex as, “My clitoris. Pushing against my jeans, firing sparks of confusing sensation up my spine.” As far as I can tell, Jefferey Eugenides is not intersex. Though he could certainly be like me, perfectly capable of passing as a cisgender man. Perhaps that’s why he wasn’t able to capture living in the body of Cal. Perhaps it was well in his capabilities but was an artistic choice to keep a little psychic distance. Either way, I’m glad he wrote about it, about the intersex experience. To see something tangential to my own experience on the page, and not just something I wrote, was so meaningful. So important. And it won’t be the last intersex fiction I read. I will search other pages to find that bodily experience represented.