For example, I could tell you that my head hurts. It would be accurate enough. I could even say that it feels like a dull throb, a splitting headache, or a 5 on a scale of 1–10. But none of these describes what, specifically, the pain feels like. I used to have a body not in pain, and now I have a body in pain. It has changed my body, and so it has changed my relationship to my body, and so it has changed the things I notice and the way I move through the world. “This hurts” does not begin to describe it. In The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World, Elaine Scarry (1985) writes that “physical pain does not simply resist language but actively destroys it.” A fundamental part of lived experience makes words flee on sight. How can such a universal experience—universal, because all animals are capable of feeling pain, not just humans—be so isolating and unspeakable?

Writing Pain: I Sure Tried

I recently finished writing a story about a medieval mystic woman. In my research, I read that in the European Middle Ages, women mystics proved their connection to God via physical suffering. Christopher Roman (2005) writes that this was because the intellectual task of interpreting God and the Bible was restricted to men, whereas the body and the senses became women’s religious domain. To be fair, Christianity is founded entirely on an instance of profound violence upon a singular body. However, in the Middle Ages, women’s bodies in particular became the physical material of devotion. Catherine of Siena starved herself to death in 1380. Beatrice of Nazareth wore a girdle of thorns. Many reported instances of stigmata. Interestingly, many mystics were also writers. They produced some of the only texts written by women at the time that still survive to this day. At a loss for how to describe the pain my main character suffers in her visions, I did more research. I read poems and articles about pain and how it works. I spent far too long doing the lazy-writer thing of looking up synonyms for words like “hurt” and “burn,” finding every word laughably ill equipped. Though I meditated on my own experiences of pain, I could not quite summon the words to recreate my memories of events such as an ovarian cyst (age 15, deliriously painful), breaking my toe the first week of college, or slamming my fingers in a hard wood door. This is not to say that the causes of pain are especially difficult to write. There is plenty of gory literature out there that is full of details of bodily harm, and you can check out this post for an overview of the literary genre splatterpunk. Pain itself, though, evades easy description.

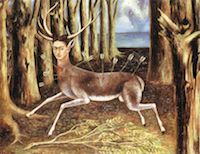

Images of Pain

Movies and television have the advantage of using the visceral and immediate medium of images. They seem to speak the language of pain far more easily than words. I remember a very specific moment from the crucifixion scene in The Passion of the Christ (2004), which I saw in sixth grade. A description of the moment itself is not necessary here, mainly because the movie sucks and Mel Gibson sucks. But it was brutal and extreme, and it imprinted on my brain for myself to return to 15 years later. Even as I write that last sentence, I am all too aware of the inadequacy of my chosen words. “Extreme” is relative: without any kind of qualifier, it has no meaning. “Brutal” has a similar issue. I might not be able to fully describe it, but the scene stuck to the weird fly trap paper of my 12-year-old brain and I remember it still. Are images the best language for speaking about pain? Maybe, but there’s a problem. Scenes of extreme suffering in movies and television position us as observers. Torment depicted on a screen becomes an object for our viewing. It doesn’t let us get inside of the pain; indeed, pain becomes spectacle.

The Problem of Metaphor

Due to its personal and internal nature, pain can be difficult to describe. Many turn to metaphor: choosing an unlike thing to represent something else. Author Julie Rehmeyer (2018) remarks that “it probably doesn’t mean much to say…that my brain feels inflamed. Instead, I might describe it this way: ‘My brain feels like an overripe peach, bruised and delicate, its juices threatening to seep out my ears.’ Hopefully that gives a visceral sense of the sensation…” You can read more about how she and other women authors approach writing pain with language and metaphor in this fantastic post over at Literary Hub. However, some issues arise with metaphor, especially in the medical world. Dhruv Khullar (2014) writes about the common positioning of someone suffering from a serious illness as a “fighter.” We’ve heard this a million times: he “lost the battle” to cancer. She’s going to “beat this thing.” Khullar wonders if this military language causes individuals to believe that if they become more sick, it’s because they simply did not “fight” hard enough. Did not try hard enough to beat the enemy illness. In other cases, though, metaphor has proven itself invaluable in conveying the experience of pain. For example, many individuals who suffer from chronic pain use a metaphor of spoons to describe limited amounts of energy that one spends throughout the day, often leaving them depleted. You can read more about the utility of this metaphor and how it came to be popularized here. Metaphor can give language where previously there was none. It can also unfairly position a person and their illness as adversaries at war. If not through metaphor, how can we write and understand pain?

Writing Pain, Discovering Worlds

So, which is it? Is pain inherently indescribable and devoid of language, or have we just not been trying hard enough? Elaine Wells (2018) of the Los Angeles Review of Books proposes that, contrary to Scarry’s assertions, perhaps it is not language itself that is insufficient. Perhaps it is our own attitudes towards pain that prevents us from finding the words. In “On Being Ill,” Virginia Woolf (1925) wonders about how literature recoils from lingering on illness: Illness and pain are such powerful and world-shifting states of being that it seems odd to not center them in literature. Like Scarry, Woolf reflects that this is due to a “poverty of language,” and she suggests that English must invent new words entirely in order to convey the experience of illness. However, while Scarry argues that pain obliterates the sufferer’s sense of self and of their world, Woolf believes that it unearths new “wastes and deserts of the soul.” To Woolf, pain and illness allow an individual to see worlds and truths that someone in health never could. Surely, this makes the task of writing pain not only possible, but urgent. In health, Woolf writes, people are able to ignore the body in favor of the mind. In illness, however, that pretense is shattered, and the workings of the body are deeply felt. For example, in Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward (2017), Leonie reflects that “pain…can eat a person until there’s nothing but bone and skin and a thin layer of blood left…it can eat your insides and swell you in wrong ways.” Pain reminds you in the most explicit terms possible that you are made out of distinct materials: bone, skin, blood. You are not one whole, cohesive person anymore. You are made of parts, and you have very little control over them. Woolf writes that “in illness…words give out their scent” in ways they do not in health. Poems, Woolf says, are especially fertile ground. With this in mind, I will close with a poem. Emily Dickinson (1890) writes: The word “blank” recalls Scarry’s argument that pain erases everything in the world that is not pain. However, by noting how pain disrupts time’s steady progression, Dickinson forges a new understanding of pain. She finds the language to describe it as its own future and past, extending forever into “infinite realms.” Furthermore, she does not describe pain as it relates to her experience of it; not once does she use a first person pronoun. Pain overtakes the self. There’s no room for anything else. Even while marking the blankness and the absence of a self in pain, Dickinson has given words, and therefore a form, to that blankness and absence. The need to describe pain is urgent. Language is imperfect, but it’s the tool we have to remake a uniquely isolating experience into a point of connection, compassion, and empathy. This is creative work, giving shape to what is shapeless. Pain is a shadowy world that we all walk through alone. It would be nice to know that other people understand what it is to walk through it, too.