This 7% are, according to 2017 PEW Research Center data, made up of some 12.3 million people living in the United States who are immigrants with permanent resident status, and the 10.5 million people living in the United States who are undocumented. Combined, this totals 22.8 million people who call the United States their home, but are ineligible to win one of the nation’s highest literary honors. Of course literary awards, like any other prize or competition, must have rules. Eligibility requirements also put parameters around things like the dates between which a book has to be published for eligibility in a certain award year, for example. But why is citizenship used as a rule? This piece examines the eligibility requirements of five major literary awards: The Booker Prize for Fiction, the National Book Critics Award, the PEN/Faulkner Award, the National Book Award, and the Pulitzer Prize, specifically looking at their positions on citizenship in relation to prize eligibility.

Questioning the Citizenship Metric

The way these awards handle citizenship as an eligibility requirement varies widely. Two of these awards are, in a sense, “borderless,” with no nationality or citizenship requirement among their eligibility standards. Two more of these awards used to require United States citizenship for eligibility, but have since amended their requirements—though with differing new requirements now in place. And one award—as mentioned above, the Pulitzer Prize—still has a hard citizenship requirement for eligibility as of 2020. In my personal opinion, citizenship to a certain nation is an illogical way to determine who does and who doesn’t have access to certain artistic honors. I want literary awards to recognize the quality of a great work of art. What does citizenship to a country tell us about the value or the quality of a work of art? Personally, living in this increasingly globalized world, I don’t need my literature to represent “Americanness,” to be award-worthy, I just want it to portray the best stories and personal experiences. And don’t just take my opinion on this; Kazuo Ishiguro—who has won both the Nobel and Booker Prize for Fiction—agrees, stating when the Booker Prize for Fiction, in a sense, went global, that “the world has changed and it no longer makes sense to split up the writing world in this way.” Now, that’s my opinion on the role of prizes. But, these literary prizes have been around for many years and have long traditions. Some constituents and readers may disagree, and they may look to prizes as a way to define the epitome of a nation’s current artistry or culture. Those readers may believe that a national prize exists for the purpose of saying “this book is the best of America we have to offer” and may wish for a prize to stay oriented to the boundaries of a certain nation for that reason. But still then, citizenship is not a valid metric for determining the best of America, or American literature. We can agree or disagree on the role of literary prizes, and whether they should be specific to certain nations or not, but what cannot be debated is someone’s belonging to this country, and how that belonging must be separated from the concept of citizenship. Because there are many problems with the United States citizenship process, and as a result many people living in the United States have not been given a fair and accessible path to citizenship, even if they wish to become naturalized citizens. However, their lived experiences happen on the same soil as others living in this country. And just as anyone else living here, they have American experiences and American stories to tell. Their art can, and does, reflect those experiences, their citizenship notwithstanding. And yet, citizenship still plays a role in eligibility for many literary prizes. Let’s examine the prizes and see how they handle this requirement.

The Booker Prize for Fiction

First, the Booker Prize for Fiction—previously the Man Booker Prize—which was established in 1969. For the first 45 years of this prize, eligibility was open only to authors from Britain; Ireland; the Commonwealth—a collection of 54 member states, nearly all former colonial territories of the British Empire; and also Zimbabwe, which was still an official British colony until it gained independence in 1980. But in September 2013, the Booker Prize for Fiction drastically changed its rules. The prize extended its eligibility criteria to accept any novel originally published in English by a UK publisher during the timeframe of the annual award period. This made the prize essentially “borderless,” opening it up to any writers across the globe originally publishing in English. It is also worth noting the foundation added an International Booker Prize for books in translation in 2005. It was still a few years before that rule change had an impact on the award results. The rule change first came into play in 2016, when Paul Beatty became the first American author to win the Booker Prize for Fiction for The Sellout. Then the next year, the American author George Saunders won for his novel, Lincoln in the Bardo. At first look, I thought the rule change came into effect again in 2019—when the prize was split between Bernardine Evaristo for Girl, Woman, Other and Margaret Atwood for The Testaments—because Bernardine Evaristo is British (and also the first Black British person to win the Booker Prize for Fiction), and Margaret Atwood is Canadian. However, Canadians like Atwood were already eligible for the Booker Prize for Fiction before the rule change, because of Canada’s membership in the Commonwealth. No doubt the 2013 rule change drastically shifted this long-established award. And though this more “borderless” approach to evaluating art is my personal preference for literary awards, the rule change has not been without critique from the wider literary world. In 2018, a letter signed by 30 members of the book industry circulated to the Booker Prize for Fiction board, calling on the prize’s board to reverse the 2013 rule change. In their letter, these industry insiders claimed: “The rule change, which presumably had the intention of making the prize more global, has in fact made it less so, by allowing the dominance of Anglo-American writers at the expense of others.” At the time of the letter’s circulation, half of the prize winner’s since the rule change went into play had, in fact, been American writers. The Booker Foundation countered that the four year sample since the rule change was too small, and the intent of the rule change was not specifically to include American writers, but to allow writers of any nationality, regardless of geography or citizenship, to be eligible for this elite prize. The prize has not made changes to its eligibility requirements regarding citizenship since the original 2013 changes.

National Book Critics Award

The Booker Prize for Fiction is not the only prize to disregard the concept of borders. For example, another prize that neither goes by nationality nor requires citizenship is the National Book Critics Award, which was established in 1976. This award is the only national literary award chosen by book critics working in the United States book industry. And though nominations are made by people working in the United States, and it is technically an “American” prize, there are no restrictions on National Book Critics Circle membership based on the participating critic’s citizenship, or even country of residency. Nor is citizenship used as a determining factor for a book’s eligibility. The award’s mission is, put simply, “to celebrate the finest books published in English” in a certain year. Interestingly, the 2018 winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award was Irish writer Anna Burns, author of Milkman, who also won the Booker Prize for Fiction in that year. Perhaps opening up all literary prizes on a globalized scale, by way of the Booker Prize for Fiction or the National Book Critics Circle Award, risks creating a more “homogenized literary future,” as those industry insiders warned in their 2018 letter. This is certainly one argument made by those who would rather see awards separated out, to find the “best” of distinctly American literature, or distinctly British (plus Ireland, and 55 Commonwealth nations) literature. Two awards on this list differentiate themselves in this way, as distinctly “American” literary awards. But, crucially, they do so without strictly requiring United States citizenship for eligibility. What does this mean in practice? Well, it varies between the two awards.

PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction

First, take the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, which was established in 1980, and is the newest prize on this list. For 38 years, the prize required United States citizenship for eligibility, but in 2018 the PEN/Faulkner’s Board of Directors made the decision to change the citizenship requirement for the award to include “American permanent residents and Green Card holders.” Shahenda Helmy, the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction’s Programs & Logistics Director, told me, “We implemented this change in order to make the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction more inclusive and accessible as well as reflective of the true landscape of American fiction.” If we refer back to the PEW Research Center data at the start of this piece, this award’s rule change allowed access for the 12.3 million people living in the United States who are immigrants with permanent resident status to be nominated for the award, but it still does not include the 10.5 million more people living in the United States who are undocumented, even those who wish to become United States citizens but have not been given an accessible path to citizenship. In practice, this eligibility change is certainly a step toward increased accessibility, though the exclusion of Americans who are undocumented still leaves out people who are arguably no less a part of the true landscape of American fiction. Also worth noting is that unlike the Booker Prize for Fiction, where award outcomes have been radically different due to eligibility changes, the eligibility change for the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction has yet to impact the actual outcome of the award. Helmy confirmed that, “as it happens, in the two years since we changed the eligibility requirements, all of our finalists have either been U.S. citizens or have held dual citizenship.”

National Book Award

Which brings us to the National Book Award, an award established in 1950 whose mission is to “celebrate the best literature in America.” The National Book Award also amended their citizenship eligibility requirement in 2018, though due to the timing of the eligibility changes and award announcements, the National Book Award is currently in the middle of its third cycle with their new eligibility rules. According to their website, the new eligibility requirements read as follows: “For the Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry, and Young People’s Literature Awards, authors must be U.S. citizens, or if authors are non-U.S. citizens or have particularly complex immigration issues, there is a petition process. In the case of authors for whom this would apply, publishers must contact us directly and answer the following questions:

Has the author lived in the United States for 10 or more years as of November 30 of the Awards year? Does the author consider themselves: an American immigrant who is currently and actively engaged in pursuing citizenship, OR legally unable to pursue traditional pathways to citizenship at this time?”

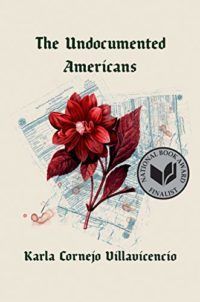

I spoke with Lisa Lucas, the Executive Director of the National Book Award, and she emphasized that it is publishers who supply responses to the two extra questions listed above that consist of the foundation’s “petition process” under the new eligibility rules. She said these two questions were intentionally chosen to be short enough not to create additional barriers for nomination of non-citizens, while also still allowing for boundaries around the award that keep it defined distinctly as a “best literature in America” award. Like the PEN/Faulkner Award, accessibility was also the primary reason Lucas gave for changing the eligibility requirement, saying, “From our perspective, the requirement ‘you must be a U.S. citizen’ was far too limiting because there are so many people who do not have access to citizenship, but who are very much a part of our literary landscape, without question. Our belief is that you cannot do a prize for American literature, and do it based on citizenship.” So, in 2018, the foundation moved forward, “with expert guidance,” according to Lucas, to adjust their restrictions. And those eligibility changes have in practice changed the landscape of the resulting nominations. In the current National Book Award cycle—results of which will be announced on November 18, 2020—Karla Cornejo Villavicencio has been shortlisted for the National Book Award for Nonfiction for The Undocumented Americans, making her the first writer who is undocumented to be nominated for this, or truly any, major literary award. Her accomplishment is historic. But Cornejo Villavicencio commented on an Instagram post that she was having a difficult time speaking publicly about her historic nomination, which was announced around the same time ICE had been accused of forced sterilization of their detainees. Cornejo Villavicencio felt cognitive dissonance between the revelation of these atrocities against humanity happening on United States soil, and the celebratory news of her recognition for writing a book about the very humanity of undocumented Americans in this country. But Cornejo Villavicencio did go on to say in her post that, “I’ve recognized, after speaking to some people close to me, that this nomination means a lot to the community. The Latinx community doesn’t see recognitions like this very often in the elite art world. I am the first undocumented writer to be nominated for a National Book Award, and to not report that as a historic event would be another erasure for our community.” Though the National Book Award’s eligibility changes have opened up access and allowed for this historic nomination, some readers still view the award’s “petition process” as a form of gatekeeping that could still create barriers to nominations for non-citizens. A Change.org petition is currently being circulated, stating that “there shouldn’t be a ‘petition’ or even a further process to prove that undocumented people are a part of this nation.” When asked about the Change.org petition, and if the National Book Award is open to reviewing their eligibility requirements—including the “petition process”—again, Lisa Lucas expressed openness, saying, “In the years I have been at the National Book Foundation, we have tried our level best to be the kind of organization that listens, that responds, and that cares,” and went on to say, “I may not be in place [Lucas has accepted the role of Senior Vice President and Publisher at Pantheon, and will exit her position as the Executive Director of the National Book Foundation at the end of 2020], but the openness to having rigorous conversations with people, has been how we have developed everything we do at the foundation.” And on behalf of the Foundation, Lucas expressed no sense of inflexibility or resistance within the organization’s leadership with regards to eligibility changes that were previously made, or could be made in the future. Lucas emphasized, “It’s not a static prize. Everything doesn’t stay the same forever. The reality is, you make changes, and it works or it doesn’t work, you maybe adjust it, and you work with constituents through it. You often have to be both reactive and reflective doing this work.” She feels the objective going forward should be to determine “how to use the most inclusive and kind language possible, even when you must still enforce rules.” Ultimately, the purpose of the National Book Award’s 2018 rule change was to acknowledge what it truly means to be part of our American literary landscape today, understanding that citizenship is an outdated eligibility requirement and an inaccurate way of defining “Americanness.”

Pulitzer Prize

That brings us to the Pulitzer Prize, which is an award “for achievements in newspaper, magazine and online journalism, literature and musical composition within the United States” that has been around since 1917. The Pulitzer Prize draws a hardline requirement on citizenship, stating on its website: “Only U.S. citizens are eligible to apply for the Prizes in Books, Drama and Music (with the exception of the History category, in which the book must be a history of the United States but the author may be of any nationality). Permanent residents are ineligible. For the Journalism competition, entrants may be of any nationality but work must have appeared in U.S. newspaper, magazine or news site that publishes regularly.” Put simply, these eligibility requirements do not reflect a contemporary landscape representative of our nation. The Pulitzer Prize is the longest standing literary prize we have examined in this piece, and these archaic eligibility rules should be examined to reflect, as Lucas said, that “things don’t stay the same forever.” Ultimately, after reviewing just these five prizes, the purpose of this piece is not to be the one answer saying which literary award “got it right,” or which award “got it wrong.” As a privileged white woman whose citizenship or resulting “Americanness” has never been called into question, it would never be my place to evaluate such rightness or wrongness in that way. And while as a reader I have expressed preference for the mission of literary prizes to be more global, I again want to be clear—preference can apply to the function and mission of prizes, but a personal preference doesn’t come into play when determining the validity of someone’s “Americanness.” These two things are separate—you can want certain prizes to stay the same and to recognize the “best of American literature” and still call for a contemporary examination of what that really means. And, readers, you should. What this piece does strive to do is make you aware of how literary awards determine eligibility. To draw attention to who is included, and how is excluded. To help you make your own assessments, and ask more questions. That may mean you’re asking certain awards to do better. It also means that even when changes are made, we can never consider these conversations complete. There should always be room for continued evaluation, and openness to change the way we recognize and celebrate great literature through awards. These issues are complex, but that can’t stop us from engaging with them, and continuing to examine and hold them up to new and contemporary standards. After all, as readers, we know the importance of this best of all.