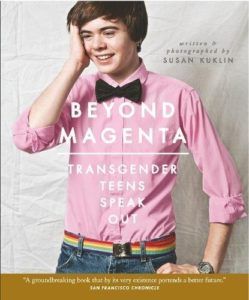

Last month I was idly scrolling the reams of tweets when one caught my eye, and then made me scowl. Beyond Magenta, a book which details the formative experiences of young transgender people, had been removed from the children’s shelves in a Cork City library. It was reported by Pink News, a prominent LGBTQIA online magazine based in the UK, a few hours later. Beyond Magenta was published in 2014 by Susan Kuklin, and is made up of a series of interviews with trans teenagers about their own life experiences. It’s always been controversial for far right campaigners who have long sought to ban it. In the case of the library in Cork, the book was deshelved following a letter from one such campaigner. The campaigner’s first name is Kelly but she kept her last name private. Her letter stated that the book ‘normalises abuse and even paedophilia’. Kelly also lashed out at drag queen story time events and went on to say that LGBT+ people should be vetted by police before being allowed to read to children. Cork City Library removed the book from the children’s shelves and recategorised it as YA/Adult, meaning an adult needs to okay it being removed from the library by a young person. Given the difficulties faced by many young people struggling with gender identity, particularly where friends and family may not be supportive, removing an honest book about a less explored experience seems cruel. I come from Cork. I grew up there. I spent my young years in Cork City Library, perusing the shelves for the next great adventure. As a child, I read anything I could get my hands on, and nobody ever questioned my choices. Arguably this was because the books chosen for the children’s section had already been through a form of gatekeeping, with categorisation to help point readers (and their families) in the right direction. But I was a child in the 1990s, when issues around gender expression, sexuality, identity, and even consent weren’t part of the mainstream discourse in Ireland. I’ve written for Book Riot before about how manuals around family planning were banned in Ireland, and censorship has long played a role in the conservative backdrop of the state. As a child I had no concept how seemingly innocent gatekeeping might have impacted me. As an adult, I’m furious that interference by a lone far-right campaigner can directly deny a young person access to a text that could help them work out who they are. I acknowledge also that some books may not be suitable for children, of course. Though I’m not a librarian, I know that their role is crucial in children’s literacy and that a book might suit different readers at different times. The author Philip Pullman pushes back against His Dark Materials being filed into an age based category, and has actively campaigned against age branding of books. He’s not suggesting that we force 8-year-olds to read Lolita, nor does he have an issue with people recommending his books for a certain age range. As part of the No to Age Banding campaign in the UK, he said, “I did not intend the book for this age, and not that; for one class of reader, and not others. I wrote it for anyone who wants to read it, and I want as many readers as I can get, and I want to meet them honestly.” When it’s a question of the suitability of Lyra Silvertongue’s journey to Svalbard, Pullman’s point is friendly and polite. A general person on the street might even wonder if he was too excitable, to be annoyed at the insertion of an Age Band on each of his books. After all, what harm could that do? But when we think a little further, in the wrong hands, age banding can instil limits. In Cork City Library, one person’s moral judgement of appropriateness limited access to a crucial work about gender, thus preventing people from key information that could be relevant to their actual lives. Pullman was excitable in his efforts against Age Banding because the long term implication of it is deeply problematic. Any gatekeeping of books on an age level requires an objective selection of categorisation, and that objectivity doesn’t seem to exist for books which come from the margins. A harsh fist of public morals almost always serves to diminish opportunities and equality for the smaller, less powerful voices. One campaigner can make a significant difference if she’s loud enough — even when we don’t know her surname, her motivations, her biases. That’s a scary concept, and very far removed from a conversation about whether Lyra is too complex for a 6-year-old (though you might recall that The Golden Compass film derived from the series was criticised for its moral choice to remove the anti-religious elements from the story). Beyond Magenta is most definitely an honest and revealing look at gender expression and sexuality among young people. It confronts sexual abuse head on, and removing it serves only to remove crucial information and understanding from those who might need most to read it. Transgender people deserve better, particularly young people. We as readers, writers, publishers and librarians have a chance to ensure that knowledge is available, accessible and open to all. Censorship has no place in our libraries.