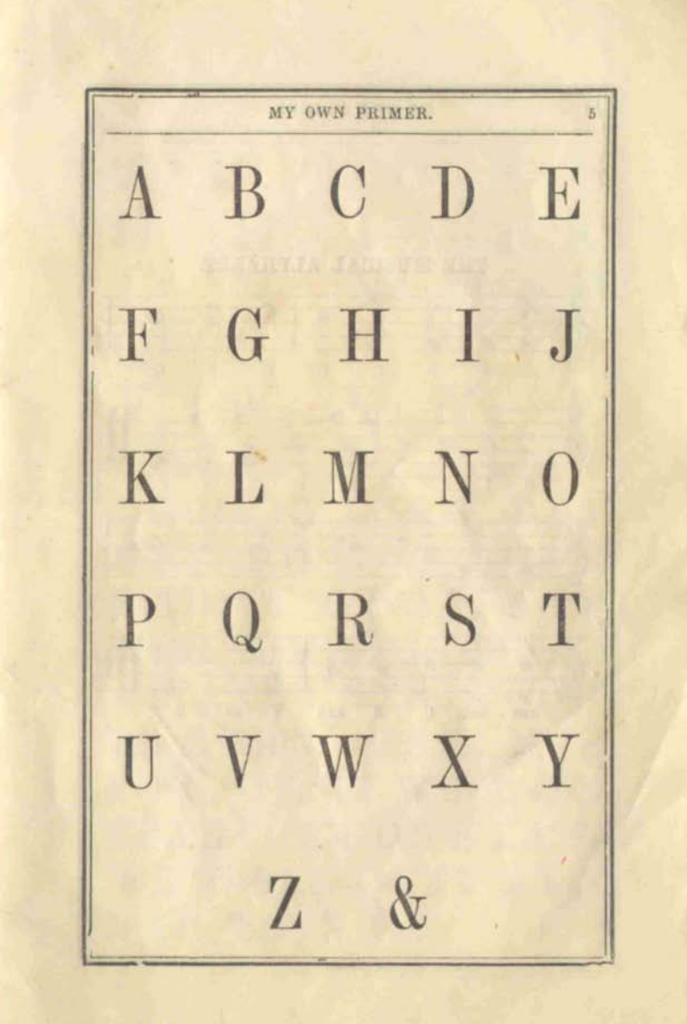

The ampersand is a cool symbol, with a wide range of typographic options available to it. And the further you dig into those options, the more apparent the symbol’s historical origins become — and indeed, this contributed to the time it took for me to choose which type of ampersand to permanently attach to my body, as the meanings were multiple. An ampersand represents the word “and,” and it’s common across Romance languages. Its origins begin in Pompeii, around the first century CE. It wasn’t, though, the ampersand with which you might have familiarity. Rather, it was two letters joined together: E and T. Et in Latin is the word and, and when found on the Pompeian wall at that time, the letters were joined together in such a way to look like a symbol. Take a peek at the above graphic, created by Open Source Ampersands, a web resource of singular symbols available for free use. It becomes clear when you peruse a variety of fonts that the “et” becomes more or less visible, depending upon the way the sign is situated. Et is seen most clearly on the eighth example on the bottom row, but it’s possible train your eye to identify it even in modern typefaces. Think of the e and the t as set atop one another, rather than side-by-side, and suddenly it’s visible in every iteration of the symbol. Despite what the & symbol stood for and meant in Latin, it took hundreds of years to become a well-recognized stand-in for “and.” Its rival was a now-unused symbol ⁊, the Tironian et. The ⁊ was developed before & appeared, by Cicero’s enslaved secretary Tiro, who’d developed a shorthand system himself called the notae Tironianae. This system included at its peak over 13,000 symbols, though most fell out of use around 1100 CE. As ⁊ and other notae Tironiane fell out of favor — except in Ireland, where it’s not uncommon to see ⁊ used in Gaelic signage — the ampersand had room to step in and thrive. The use of the symbol was so ubiquitous by the nineteenth century that it earned distinction as the 27th letter of the alphabet. This wasn’t a universal inclusion, as the English alphabet had yet to be standardizes in this time period, but numerous children’s primers and readers, as well as school curricula, included & at the end of the alphabet. Though it’s no longer in favor, when spelling out words or learning the English alphabet, letters that could also be words in and of themselves (think “a” and “i”) would be preceded with the phrase “and per se” (“and per se a,” “and per se i”). This carried forward with &. Recitation of the alphabet meant no longer ending on z, but rather the phrase “and per se and,” how the ampersand was pronounced and distinguished. “And per se and,” said aloud enough makes it clear why and how the name ampersand came to be. “&” as a letter showed up in books and in nursery rhymes, including the popular rhyme “A Was An Apple Pie” : “A was an apple pieB bit it,C cut it,D dealt it,E eat it,F fought for it,G got it,H had it,I inspected it,J jumped for it,K kept it,L longed for it,M mourned for it,N nodded at it,O opened it,P peeped in it,Q quartered it,R ran for it,S stole it,T took it,U upset it,V viewed it,W wanted it,X, Y, Z and ampersandAll wished for a piece in hand.” In 1837, the word ampersand entered the dictionary. It’s difficult to say when & lost its distinction as a letter of the alphabet, but many scholars of etymology believe it reached its peak around the 1830s, falling away from inclusion in the English alphabet later on in the 1880s or 1890s. Its inclusion in the dictionary may have signaled the beginning of the end of its place in the alphabet. Likewise, the fact that it wasn’t universally acknowledged as a letter of the alphabet may have played a role in its disappearance, particularly ass the alphabet became standardized. Others speculate that the ABC song we’re all familiar with — which shares its tune with “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” and Mozart’s “Ah vous dirai-je, Maman” — earning copyright in 1835 may have impacted the symbol’s alphabetic inclusion. Most likely, it was a result of all of the above. But & losing its designation as a letter didn’t stop the symbol from use throughout the 1900s and into today. In 1899, it was included in the Concise Manual on Typography as a sign interchangeable with the word and. Today, the symbol takes on a number of common usages with some interesting distinctions:

Business names: We’re familiar with Barnes & Noble, Tiffany & Co., Johnson & Johnson, and more.

Film credits: The & in film credits is specific in use in that it suggests a closer partnership between people than a simple “and.” If two writers worked closely on a script, for example, they’d be credited with an &. If their relationship was more in line with what an author and editor do, they’d be denoted with an “and.”

Shorthand for etc: A little more nerdy Latin knowledge for you here! Et cetera is “and so forth,” so when designated with the symbol &, it comes with the addition of a c, “&c.”

English utilizes many symbols, but the ampersand stands alone in its history, length, and popularity of use. Designers love to use it today and develop creative means of showcasing the symbol across a wide array of fonts. Want more reading about letters and symbols of the alphabet? You’ll want to pick up Clash of Symbols. A Ride Through the Riches of Glyphs by Stephen Webb and Shady Characters. The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols & Other Typographical Marks by Keith Houston. Then, of course, get to know the answer to where, how, and why the letter W may be considered a vowel.