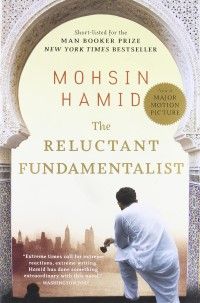

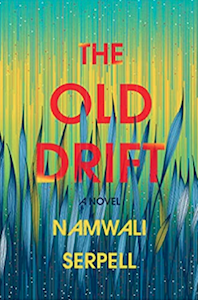

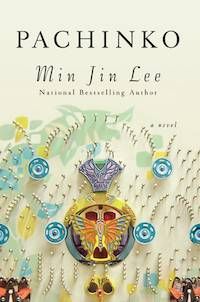

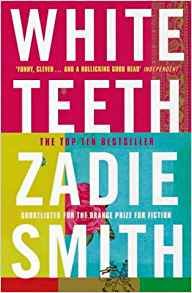

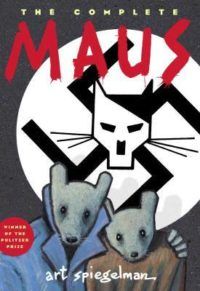

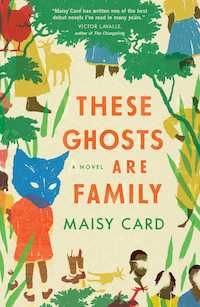

These books are often concerned with power, identity, and privilege. They recognize the complexities of belonging, from minority or under-represented perspectives. And they may reveal as much about the “host country” as about the “home country” (while recognizing that these concepts are fluid and often flawed). The novels that I find most revealing about British identity, for instance, are by immigrants and the children of immigrants. This is a list of the novels that have most shaped my thinking about diasporas. Many of these characters are affluent, which reflects the privileges inherent in who is allowed to move freely in the world. There’s also a clear bias toward U.S. and UK books. This suggests the outsized role that the United Kingdom and States play in migration stories, particularly those written in English, but also my personal history as a dual citizen of these two countries. In The Reluctant Fundamentalist, upwardly mobile cosmopolitanism is key to the protagonist’s identity. It also feeds the sense of injustice that ultimately leads to violence. This slim, elegantly disturbing novel is essentially a long monologue. That makes it feel uncomfortably intimate to follow Changez’s path from a glittering career in international finance to disillusionment with Pakistan’s manipulation in international relations. Changez’s epiphanies come through travel and intercultural contact, making it a novel about movements in multiple senses. The Old Drift is stunning in its historical sweep, even as it questions the way history is packaged for different groups of people. This history is heavily marked by colonialism and resistance to colonialism, with some fascinating detours: the teenage “Afronauts” of Zambia’s 1960s space program (true), and the mosquito-mimicking drones and ubiquitous human microchips (not yet true). Countries of origin, for these Zambian characters and their ancestors, remain close at hand – provoking guilt, nostalgia, pride, confusion, and many other emotions besides. Affluent East Asia isn’t always considered part of the postcolonial world, yet as Pachinko meticulously details, colonization has strongly shaped Korean identities and relationships with neighboring countries. The Korean family in Japan faces many indignities because of their origin, from being segregated in squalid housing to being forced to take Japanese names. And the younger generations, rather than casting off their outsiderness, make dramatic choices to accommodate it. White Teeth knows to the bones how it feels to have conflicting loyalties. These aren’t just about religion and nationality, but also about ideology and kinship – things that can switch from ambivalent to fervent in the twitch of an eye. The novel is also very funny in its exploration of multiracial, multicultural London. This genre-spanning graphic novel finds novel ways to convey not just the horrors of the Holocaust, but also the generational legacies of that trauma. The first volume is subtitled “My Father Bleeds History,” which is an apt description of the ways that displacement can continue to leak out and reveal itself, even decades on. This epic novel unspools the long tails of trauma and love in families webbed among the UK, Jamaica, and the U.S. These go forward and backward in time among, for instance, slaveowners, healthcare aides, addicts, lovers, and, yes, ghosts. The experiences of the Jamaican middle class characters, who find themselves in lowlier circumstances in the U.S., attest to the complications of status in a migratory world. Kunzru writes brilliantly about Britain’s attempts to remodel India partly in its own image. This extends even to the manicured English gardens that just don’t work in the Indian climate, but that many elites in India insist on regardless. But The Impressionist also explores colonialism’s efforts to penetrate the minds of the colonized, for example through English children’s books presenting a romanticized view of Jolly Old Blighty to distant slum dwellers. The multiracial protagonist of The Impressionist absorbs new names and identities as he crosses borders. His shapeshifting is both riotously entertaining and a useful metaphor for the unfixed nature of identity. We Need New Names is both the title of a brilliantly poignant novel and an effective description, just on its own, of the complexities of migrant identity. Darling grows up in a precarious Zimbabwean settlement full of both fun and trauma. She and her friends long for the imagined wonders of the US, but after she actually arrives there, sadness continues to shadow her life. Finding a secure place in the world, she realizes, is about more than just physical security of housing.