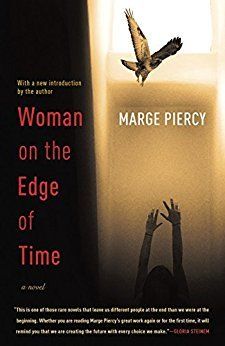

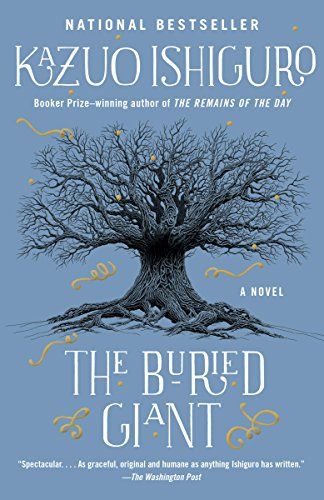

But I do think that there are some books out there that are just made to be reread. These books are twisting, turning, meta miracles: books that can be appreciated even more on the second read, when you’ve reached the end and can double back, connecting clues and motifs, discovering small riddles and magical turns in the author’s work. They are books that reveal so much by the end that you want to go back and look for clues; they are books that ask so many questions that you want to search for the answers; they are books that are so meta, they don’t have traditional endings at all. I’m a big fan of these strange, twisting reads, and you might be too. So if you love the annotations, the flipping back and forth, unfolding mysteries behind your hands, finding clues that you didn’t see on the first read — if you love all of those, then these books to reread are certainly for you. But Nabokov meant for this book to be read more than once: he made Humbert Humbert, the pedophilic narrator, poetic on purpose — and it was not because he was sympathetic to him. He wanted to write a book where the evil is banal, and so even more dangerous, revealing how true evils and violent acts can be covered up by “pretty” language and normalized. But his goal wasn’t to cover it up well enough that it would be lost, and on second read, you notice things you didn’t before. This book is full of evidence of HH’s evil, of Dolly’s trauma, of the ways he dismisses her, renames her, abuses her — the ways that he interprets her genuine, normal emotions as illogical childishness, for example. I have read this novel five times, and each time I look back on my copy that’s worn with annotations, I find more heartbreak within it. Interestingly, some people do not read the ending as ambiguous at all, and yet many people I’ve talked to think different things happen at the end of this novel. It’s for that reason, and for the questions that Ishiguro asks, about what love is, about what we should remember in both relationships and in “larger” issues, such as war and nationhood. It’s a love story that makes you think about the cost of peace. Pavić is a Serbian poet, translator, and literary historian who uses the novel to investigate issues of nationhood, and of what happens to a nation that “disappears” — was it destroyed, or was it simply filtered, its stories warped or changed, edited, small pieces of it surviving? It is the kind of book that is strange and certainly not for everyone, challenging the very idea of what a novel could be, but I promise you this: once you dig in, just like the scholars in the novel, you will never get out. There will always be another mystery to try and solve.